In Praise of the Literary Fragment and What it Has to Do With Your Life

Or Why the Tiny Is Enormous

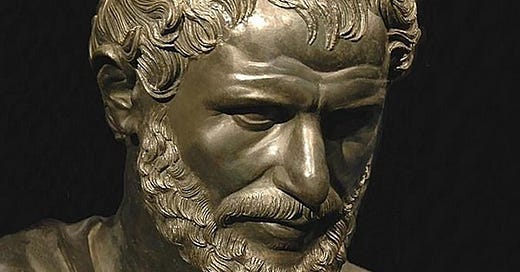

[Greek philosopher Heraclitus, one of the fathers of the philosophical fragment]

I want to talk about the “literary fragment.” I realize that a topic that may be esoteric for even many literary critics must necessarily seem completely irrelevant to your life, yet I would argue that it’s incredibly important for everyone to think about the fragment-in-general, because in our manic world we are force-fed nothing but fragments of language and images, which we are expected to quickly digest and make sense of. And often, the purveyors of those fragments have sinister motives and even more sinister ends in mind, But more on this later.

The literary fragment, in contrast to other short forms, like the aphorism and pensée, has a bad reputation, mostly, I think, because of the connotations of the word. Fragments are to some dim-witted critics “unfinished” thoughts, part of nothing substantial. Critics both now and in the past have thought that although fragments are amusing at times, they don’t teach or enlighten us, in contrast to the aphorism or pensée (the latter term which is a fancy word for “thought”). For example:

Here’s an aphorism from James Richardson’s collection, Vectors, Vectors: Aphorisms and Ten-Second Essays that seems to abide by the generally accepted definition of an aphorism as being a pithy observation that contains a general truth:

“How much less difficult is life when you do not want anything from people. And yet you owe it to them to want something.”

Next, a pensée from the philosopher Blaise Pascal, who wrote a whole book called, Pensées:

“Order.—Men despise religion; they hate it, and fear it is true. To remedy this, we must begin by showing that religion is not contrary to reason; that it is venerable, to inspire respect for it; then we must make it lovable, to make good men hope it is true; finally, we must prove it is true. Venerable, because it has perfect knowledge of man; lovable, because it promises the true good.”

And finally, consider this fragment from the pre-Romantic philosopher Frederic Schlegel, who with other great thinkers and poets from an early 19th-century group called the Jenna Romantics, brought the literary fragment to prominence:

“The most insignificant authors have at least this similarity to the great Author of the Heavens and Earth: that after a day’s work is done, they have a habit of saying to themselves, ‘And behold, what he made was good.’”

And another from Schlegel:

“One should drill the hole where the board is thickest.”

I provide two examples from Schlegel to point out that, even though Schlegel championed the “fragment,” making it crucial to how European thinkers and poets expressed themselves during his time, his second fragment could very easily be called an aphorism. Likewise, I could go through all of Pascal’s pensées and Richardson’s aphorisms and point out where many overlap with the other two genres. I could do the same exercise with Kafka’s aphorisms, some of which even morph into tiny prose poems, such his famous: “Leopards break into the temple and drink to the dregs what is in the sacrificial pitchers; this is repeated over and over again; finally it can be calculated in advance, and it becomes a part of the ceremony.”

The important point is that what critics say about one genre often can be applied to all three. Consequently, I tend to look at them all as “fragments,” since they all are indeed fragments of prose.

Schlegel himself stressed the importance of the autonomy of the fragment when he wrote: “A fragment ought to be entirely isolated from the surrounding world like a little work of art and complete in itself like a hedgehog.” Thus, he recognized that the fragment must have room to breathe, though later in life he also saw the need for it to be a part of something much bigger, a system of thought, so to speak.

As he puts it: “It is equally fatal for the mind to have a system than to have none. It will simply have to combine the two.”

That is, fragments can stand alone while also being part of a system, and in fact systems themselves are part of other systems. After all, we humans crave completeness, which is why we gravitate toward systems of thoughts, which we develop into grand narratives, such as religions, political platforms, schools of art, and so on.

Rather than going into a boring explanation of the intricacies of all of the above, let’s look at some of my favorite fragments from the notebooks of the late, great poet Charles Simic, collected in a book called The Monster Loves His Labyrinth. The Monster Loves His Labyrinth I do this partly to exemplify how the borderlines between the fragment, the aphorism, and the pensée are often nonexistent, and partly because Simic’s is a very funny guy. More important, his fragments prove that the comic can indeed be very serious, and that in the hands of a genius like Simic, the possibilities of fragments are endless. Ponder these gems:

“History is a cookbook. The tyrants are chefs. The philosophers write menus. The priests are waiters. The military men are bouncers. The singing you hear is the poets washing dishes in the kitchen.”

“Headlines in Supermarket Tabloids:

A FLY TERRORIZES KANSAS

CANNIBAL WAITER EATS SIX DINERS IN L.A.

BABY SMUGGLED INSIDE A WATERMELON”

“The new American Dream is to get to be very rich and still be regarded as a victim.”

“Snow arriving this morning at my door like a mail-order bride.”

“I always had the clearest sense that a lot of people out there would have killed me if given an opportunity. It’s a long list. Stalin, Hitler, Mao are on it of course. And that’s only our century! The Catholic Church, the Puritans, the Moslems, etc., etc. I represent what has always been joyfully exterminated.”

“To be a poet is to feel something like a unicyclist in the desert, a pornographic magician performing in the corner of the church during Mass, a drag queen attending night classes and blowing kisses at the teacher.”

“One-eyed cat in a fish store window.”

The above “fragments,” fragments that steal from so many different genres (tabloids, cookbooks, historical facts, and so on), are as isolated and complete in themselves as a hedgehog, but they are necessarily also part of a whole. Why? Because they are all filtered through Simic’s consciousness, a consciousness with certain obsessions and preoccupations. I think this is what Schlegel was referring to when he wrote, “My whole self is a system of fragments.”

Moreover, a quick look at the structure of Simic’s book, most likely decided upon long after writing a few hundred entries, suggests that he came upon a thematic arrangement before publication. This process is not unusual. It’s one that Kafka went through with his aphorisms and Pascal with his pensées.

Now what does all of this have to do with us? In a sense, even if we can’t discern an organizing principle behind a book of fragments, I think that readers create a certain order every time we try to make sense of a text by relying on all of our previous learning and personal experiences. And a truly good book offers an inexhaustible number of interpretations, which are altered every time we return to it with fresh eyes.

This is the kind of reading experience I tried to create when writing my book of fragments/prose poems, called Observations from the Edge of the Abyss. (Free Download at Observations from the Edge of the Abyss And one that I hope to recreate in future Substack posts of fragments, which will be called “Dispatches from Terra Incognita.”

In the introduction to Observations, I explain my process of composition and how I came to a kind of structure to the book. It shouldn’t surprise anyone that my process involved, paradoxically, the interplay of intuition and reason. I rely on intuition to get down the raw materials of my fragment/prose poems and then rely on improvisation, where my intuition works simultaneously with and against my intellect in an attempt to make sense of what’s on the page before me. It’s an exhilarating process.

I like to think that new interpretations are created every time Observations is read. That is, that the reader, upon multiple rereadings, will experience each fragment differently, and see how they relate to each other in each section, and how each section works with and against other sections, in a kind symbiotic tango. In the end, the reader is the architect. I’m just the dope who dropped off the raw materials one night while on something resembling a crystal meth high.

As a final word to you, my readers, please beware when you absorb all the fragments inflicted on you every day. Take your time. Examine them. Interpret them. Look at the motives behind them. It can be dangerous to let power freaks do the work for you, not to mention that it’s an insult to your intelligence. Remember, folks, there’s a hell of a lot more at stake in the real world than the literary one. Democracies can fail. Women can lose control of their lives. Poor people can become dead people.

The bad guys, and they’re usually guys, aren’t fucking around.

You can find Peter Johnson’s books, along with interviews with him, appearances, and other information at peterjohnsonauthor.com

His most recent book of prose poems is While the Undertaker Sleeps: Collected and New Prose Poems

His most recent book of fiction is Shot: A Novel in Stories

Find out why he is giving away his new book of prose poem/fragments, even though he has a publisher for it, by downloading the PDF from the below link or going to OLD MAN’S homepage. His “Note to the Reader” and “Introduction” at the beginning of the PDF explains it all: Observations from the Edge of the Abyss+