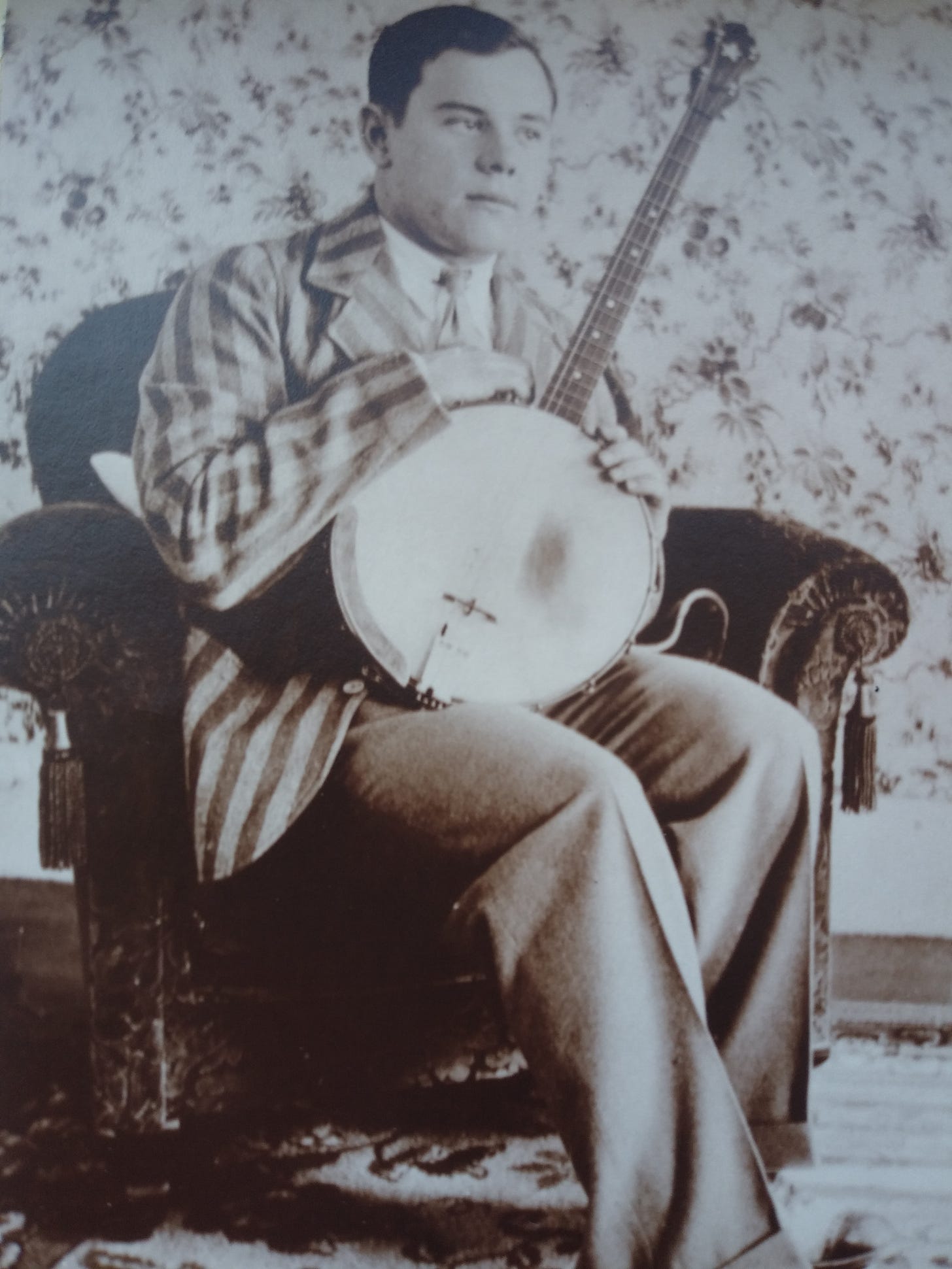

[Picture of Don’s father at the age of 20]

[A piece to think about from Don Soucy a week before Father’s Day]

"The father who does not teach his son his duties is equally guilty with the son who neglects them." —Confucius

My father grew up working class. His parents came down from northern Quebec like many others to find work in the thriving cotton mills and shoe shops of New Hampshire. They all worked hard to raise large families, buy homes, move relatives from old farms to new jobs—and were damned proud of it.

For instance, my father’s stepmother as a young girl borrowed a pair of boots from a neighbor to walk to the nearest train. She worked in a NH cotton mill that made blankets until my widower grandfather convinced her to marry him and raise his 4 young children. She scrimped and saved, and ran her home like a boarding house, keeping her pantry locked between meals. She also managed to move 9 siblings one at a time to NH. Until he finally moved out, my dad never had his own bed but shared one with whichever uncle was passing through.

For extra money, she cultivated a small, backyard garden of red raspberries, tomatoes, green onions, and a variety of herbs that she salted and sold by the jelly glass. She made and sold her own soap and the rugs she braided from scraps of cloth, and hawked pints of raspberries and tomatoes. When my father reached the eighth grade, she ended his schooling and put him out to work. She also charged him room and board.

At 15, my father entered the shoe factory that would support him for the next 47 years. He lived well during the great depression. He was young, single, had a steady job, and he knew everyone in town who sold bootleg liquor. He played saxophone and banjo and dreamed of joining a band.

My own relationship with him started out on the wrong foot. I was my mom’s first-born, but my dad’s second. My half-brother is 10 years my senior, but he belongs to my father’s generation, the one that lived through the depression and two world wars. I came two years too early to be considered a boomer, but they always saw me as part of that spoiled, noisy, rebellious crowd.

I spent summer vacations at my dad’s factory, a dusty place redolent of leather and shoe polish and sweat. My dad’s pride in his work never diminished; his new dream was to someday retire to his own cobbler’s shop. But by then, cobbler shops had gone the way of nickel beers and the Edsel.

Nonetheless, he taught me two important lessons about work. The first: when he pointed out my snow shoveling was awful, I argued I was in a rush. “If you don’t think you have time to do a job right,” he countered, “what makes you think you’ll have time to do it over?”

The second: watching him get ready for work. My first day at the factory, he got me up at 5:45, insisted that I eat a solid breakfast, and made sure we got to the shop by 6:35, even though the line didn’t start until 7:00. In the locker room, I watched as he got into his work clothes, smoked his pipe for a bit, then headed to his station. There, he organized his workspace, sharpened his tools, and when the bell clanged at 7:00, he was already on his first rack of shoes, while some of the younger guys were rushing to clock in. He never said a word, but I realized that for him work was too important to take lightly, and that you owed it to yourself—not to the foreman or even to the company, but to yourself—to take pride in what you do.

Work is also central to the most vivid recollection I have of him. The week my half-brother turned 16 was the start of an argument that would last 20 years. My father reasoned that at 16, my half-brother was ready to leave high school for a full-time job. But my mother intervened, arguing that finishing high school was important to his future. They fought for weeks, my father insisting that working-class kids didn’t need an education, while my mother pointed out that the 50’s were not the 30’s, that even working-class kids deserved a chance at something better.

My half-brother finally resolved the issue by getting a full-time job at a local garage late afternoons, evenings, and Saturdays while staying in school. He did this for two years until he finally graduated and left for the Air Force.

Fast-forward 20 years. It’s Christmas day and I am graduating from the University of Maine in January. As a Vietnam-era veteran, I had used the GI Bill to earn a BA in English. I announced that I was enrolling in the graduate program and would be looking at two more years of college. My father blew his stack. Among other things, he accused me of being too proud or too lazy to work, and then he threw me out of his house. I spent that holiday break at the Boston YMCA, watching old movies and Sesame Street.

He didn’t come to my graduation. Weeks later, he wrote to apologize. It was a sweet letter that had my mother’s touches all over it. Nevertheless, I left grad school that summer and didn’t return until he died suddenly a few years later.

All father-son relationships are problematic, I think; it’s hard to know how to be a son. Despite dizzying flights of literary fancy, James Joyce spent his entire life writing about his own father, John Stanislaw Joyce: part-time political appointee, part-time singer, full-time drunk. John Joyce abandoned his large family to poverty as he roamed Dublin, swapping colorful anecdotes for drinks. But James Joyce seems never to have lost his affection for him, and his knowing portraits of Simon Daedalus in his novels reflect this painful dichotomy, getting a kick out of his dad’s carefree ways, while recognizing the cost to the family he brought into the world.

I, too, felt I had to balance my father’s expectations with my own ambitions but didn’t succeed. I worked hard in graduate school, but he didn’t see that as real work. In the end, I wondered where we went wrong.

Enigma

My father-in-law died hoping to be rewarded for a life of self-denial until the cancer blew him away, a dried-out straw in an autumn wind. My own father died with neither hope nor consolation. His descending abdominal aorta burst like an overripe melon, leaving him to scratch his head in bewilderment. He left me his shoes, his blues, and a small measure of fear. It was little enough but all he had. So, one father lived for heavenly rewards; the other, for earthly ones. My father died before he could say it; that was his punishment. My father-in-law died saying it, which was his.

What punishment awaits me?

You can find Peter Johnson’s books, along with interviews with him, appearances, and other information at peterjohnsonauthor.com

His most recent book of prose poems is While the Undertaker Sleeps: Collected and New Prose Poems

His most recent book of fiction is Shot: A Novel in Stories

Find out why he is giving away his new book of prose poem/fragments, even though he has a publisher for it, by downloading the PDF from the below link or going to OLD MAN’S homepage. His “Note to the Reader” and “Introduction” at the beginning of the PDF explains it all: Observations from the Edge of the Abyss+